According to the most recent report from the UN Group of Experts, Rwanda has demonstrated a significant level of involvement in the two-and-a-half-year-old East Congo conflict, which has resulted in thousands of casualties and 7.2 million internally displaced people.

RWANDA

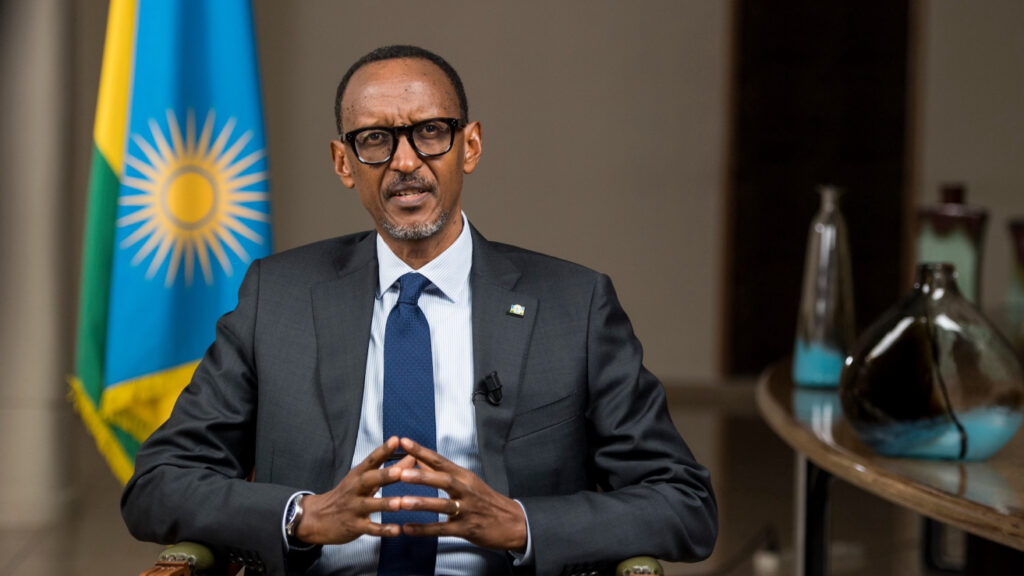

Security was the main reason Rwanda got involved in the two Congo conflicts, but Kagame was accused of making money by taking advantage of the eastern Congo’s mineral resources. A United Nations panel of specialists looked into the illicit mining of gold, diamonds, cobalt, coltan, and other profitable resources in the Congo in April 2001. The report suggested penalties from the Security Council and accused Rwanda, Uganda, and Zimbabwe of systematic resource exploitation in Congo.

Rwanda’s official statements portray the soldier deployment to the DRC as a reaction to claims of genocidal threats against the Tutsi community in the DRC. That a small landlocked nation would send up to 4,000 troops, or roughly one sixth of its military, to combat threats that the administration claims have existed for 30 years is not believable. In face of regional and global criticism, what does Rwanda hope to accomplish by providing extensive military assistance for the M23/AFC movement? Examining Rwanda’s general approach in Central Africa is necessary if we wish to attempt to comprehend what they desire.

According to a 1990 prediction by Norwegian political scientist Frank Aarebrot, African Bismarck figures would arise after Africa’s wave of “democratization.” Paul Kagame is one of Africa’s most qualified presidents; he managed to hold onto the office 30 years after assuming office by receiving more than 99% of the vote in the most recent completely manipulated elections. He developed an economic and military plan to “make Rwanda great again” over the long run. In a chaotic regional setting, Rwanda presents itself as a stable island with a business-friendly atmosphere. It supports the goal of developing into a regional center for the processing of mineral resources into valuable products. Rwanda exports significant amounts of gold and tantalum, primarily from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, without labeling them as “conflict minerals,” which is acceptable to buyers. Rwanda’s aspirations extend to Congo Brazzaville, where the country was granted an area the size of Hong Kong for agricultural exploitation; Kinshasa views this with distrust. The effectiveness of the nation’s army is its second greatest asset. The Rwanda Defense Forces have grown to be a crucial tool for carrying out elements of US, EU, and UN strategy in the area, such as the fight against Islamist activities in the Cabo Delgado region of Mozambique or the provision of troops for UN missions in the Central African Republic and South Sudan. Rwandan military are stationed in a number of interrelated theaters that support the nation’s regional power projection. The conflict in the DRC is a structural requirement because their deployment simultaneously fosters regime cohesion and protects Rwanda’s leader from hostility.

Given the scope and length of Rwanda’s assistance to the M23 movement in East Congo, it is highly probable that the ongoing fight is a long-term strategy rather than a temporary operation to neutralize the “FDLR threat.” Kagame will try to achieve all or some of his strategic goals, whether by diplomacy or the military. However, no one is certain of these goals, thus speculation is still a crucial factor. It is logical to assume that Rwanda is attempting to expand their area of stability and strengthen their influence by gaining territorial control of a buffer zone in East Congo, which is consistent with their past efforts in the region.

Their security strategy, which aims to safeguard the nation’s low strategic depth (the DRC border and Kigali are only 150 kilometers apart), and their economic strategy, which is focused on agricultural (land access) and mineral resources, are both in line with this. Scholars and policymakers who focus on Rwanda share this opinion.

Prior to the conflict, Rwanda’s merchants could easily purchase illegally obtained gold and coltan from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but now there is direct access. The 2022–2023 National Bank of Rwanda annual report states that 34% of Rwandan exports were made up of gold. It’s interesting to note that Rwanda doesn’t have any gold mines; could this be viewed as just gold being reexported? Rwandan coltan rose 49.8% between 2022 and 2023, according to data from the US Geological Survey. A direct supply route from the coltan-rich Rubaya mine to Rwanda is described in the most recent UN GOE report.

Rwanda’s extensive and prolonged involvement with an estimated 3,500 to 4,000 troops, advanced weapons such as GPS jammers and anti-aircraft systems, the appointment of a parallel administration, and the intentional burning of chiefdom archives in multiple localities are all signs that the country may have strategic goals to permanently control a buffer zone in East Congo. Additionally, it aligns with Rwanda’s regional approach. If this is true and Uganda’s helpful role is taken into consideration, this could stabilize Rwanda but not the region.

Higher ranking officers of the Rwanda Defense Forces operating in East Congo are likely to be the target of a fresh round of sanctions from the European Union, the United States, and the United Nations. The European Union, which de facto frees Rwandan finances for the DRC operation, prevented renewed funding for the RDF operation in Moçambique because Belgium refused to provide cash and some countries made it conditional on withdrawal from the DRC. Sadly, no action appears to be in the works, unlike in 2012 when aid to Rwanda was stopped and Kagame subsequently forced the M23 to evacuate the city of Goma that they had taken.

Regardless of the conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, commercial agreements are still being struck despite the mounting strain on Rwanda. In February 2024, the European Union and Rwanda signed a Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership on Sustainable Raw Material Value Chains, which included provisions pertaining to minerals smuggled from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Although transparency control mechanisms are mentioned in the framework agreement, Rwanda is said to have already rejected any such controls during the ongoing final agreement negotiations.

EUROPEAN UNION

A technocratic approach of the European Commission that disregards the political context is shown by this ill-conceived and premature Memorandum of Understanding. All other factors are separated from the race for vital minerals by the EU vital Minerals Act. There are reports that the cabinet of the European Union’s High Representative, which ought to take into account the delicate political situation, has a pro-Kigali slant.

The changed political landscape following the elections in a number of EU member states and at the level of Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, the EU’s foreign representative, might potentially put further pressure on Rwanda to leave the DRC. Negotiations are Rwanda’s only option if this occurs in order to achieve its strategic goals.

Prior accords with rebel groups supported by Rwanda in the East resulted in the absorption of their officers into the military establishments there, giving Kigali significant leverage—something the president of the Democratic Republic of Congo now wishes to prevent.

DR CONGO

Notwithstanding its inability to stop the M23/AFC, the DRC continues to wager on military support; yet, even if it begins to engage in negotiations, it is uncertain whether it will be able to escape a humiliating defeat. The DRC’s negotiation position is significantly weakened by the structural weakness of its military forces, the lack of an efficient state administration in East Congo, and internal issues President Tshisekedi faces with his own divided UDPS party and political rivals within his own coalition. Without significant international backing, mostly from the United States and the European Union but also from Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo may find it challenging to withstand Rwanda’s ambitions for influence and control in the East. It may take some time before a new EU policy is developed, and it appears doubtful that the US will be able to take a significant step before the new administration is formed.

By using his influence in France and the European Union, Kagame was able to prevent the appointment of the Belgian candidate for the position of EU special envoy, which is the cornerstone of the EU’s Great Lakes policy. By urging Monusco to expedite its departure, the DR Congo has significantly diminished the UN’s clout, perhaps undermining its own standing in the area. Because of this, Angola’s efforts as the African Union’s authorized mediator are even more crucial and essential.

Overall, determining Rwanda’s long-term strategy in Central Africa is crucial. The need for longer-term stability in the region must be weighed against the long-term effects of this policy, rather than attempting opportunistically to integrate the EU and Rwandan strategy while ignoring the tragedy in East Congo. In the name of short-term goals pertaining to mineral resources, the European Union will unavoidably be seen as a body that only upholds international law when it serves its own interests if it warns against this evolution.